Dominic Dulin is a poet and musician out of Cleveland, Ohio. They have had poetry published by Iterant, Yum! Lit, Surreal Poetics, among others.

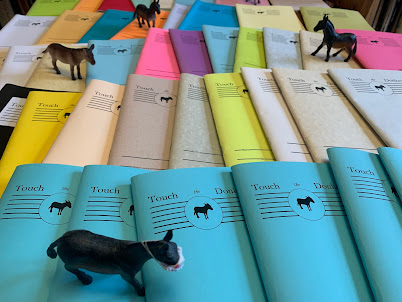

Their poems “E_nve_loped” and “Note on the Type” appear in the forty-fifth issue of Touch the Donkey.

Q: Tell me about “E_nve_loped” and “Note on the Type.”

A: Both of these poems come from the final section of my poetry book manuscript Double Time. I wrote the book during my MFA at Cleveland State University for my final thesis project. A million thanks to Caryl Pagel for being my advisor and being an irreplaceable mentor — if anyone reading this hasn’t read her work, you should.

Thematically, Double Time deals with doubling, repetition, and challenging/investigating binaries, among other themes. These poems also share those qualities with having near miss puns or direct puns in them. I also had a fairly strict line rule in the book where the poems doubled sequentially (and at a certain point in the opposite way), i.e. the first poem is in couplets, the second is in quatrains, third is in octets, and fourth is in sixteenths (which has its own fancy poetry word that is currently escaping me).

A good amount of the poems in the manuscript have glimmers of the work I was doing at the time. I had a dispatching job for hospital security and police for multiple hospitals, and while it helped me pay the bills for my fiancée and I, it eventually wore on my mental health and I became extremely burnt out. My dad is a cop and I never expected to do anything near the realm of law enforcement, and while I’m glad I know maybe a bit more than the average person about how things work in that (flawed) system, I will never do anything like it again.

For “Note on the Type”, I wanted to make a sort of anti-note poem. The Shona in the poem comes from me leafing through a dictionary and slowly attempting to learn my fiancé’s native language. A few other poems in the manuscript feature Shona and Japanese (both which I am still learning in my free time at various paces). My rule for — for lack of a better term — foreign languages, is that I tend to only want to use languages which I know or at least am attempting to learn, rather than plugging in a word from a language that I don’t know or don’t have some connection with. I love Joyce, but it seems that he may have done that at times in Finnegans Wake: plugging in words or phrases from other languages without fully inventing himself in them.

Q: How do these poems compare to some of the other work you’ve been doing lately?

A: Lately, I’ve been working on poems which are taking the form of sliced/fractured prose blocks. The first poet I read that had poems in that style is Franny Choi, who is a wonderful poet, but I’ve lately wondered whether another poet had crafted poems in the style first. I imagine the fractured prose block (as I’m calling it) has a long(er) history I’m unaware of. It seems a bit distinct from erasure poetry, which l’d imagine has an older lineage. There’s probably a Language Poet that ‘did it first’ I’m guessing. But I’m also currently interested in using forward slashes to break lines, even though the lines in the block aren’t actually broken, not unlike how a short group of poetic lines are quoted in an essay. If I remember correctly, Choi used colons, not slashes, to break up her lines.

Before that, I was working on a chapbook I’m tentatively calling “Face Notes: speak” which uses found language in a similar method I used with these poems. For both DT and FNs, I drew from line lists I either pre-wrote and let ferment, or had on hand. The main difference for the “Face Notes: speak” poems is that majority of the language comes from a text-to-speech app I was using while I was unable to talk after jaw surgery.

Q: I’m curious at the ways in which you are feeling out form. Are there other poets you’ve been attempting to learn from, for the sake of structure or approach?

A: I’d definitely say that J.H. Prynne has been a big influence. While I don’t think he always employs form in a visually obvious way, with his more recent text sequences, I do think he probably thinks about form a lot. Bruce Andrews is another poet which I’ve definitely been influenced by with some of my methods. David Melnick is another poet whose work I am infatuated with and have (hopefully) learned from. I also want to mention Oulipo — as a school of poetry I’d like to learn from — but I still haven’t dove into that realm even though my friend and poet Zach Peckham often mentions them in our conversations. Susan Howe and Hoa Nguyen are two poets I am always trying to learn from. Tristan Tzara (of course) and Bob Cobbing have influenced my interest in form as well. Catherine Wing helped me see form in a different and playful light, rather than in a wholly restrictive, outdated, or stuffy one.

To better answer how I’m feeling out form without name dropping more poets, I’d say that I’m always interested in doing something that involves numbers, experiments, and chance. Employing methods that involve various levels of (non-)control of the poetic outcomes. A sort of poetic fracturing, cut-up, or remix that resists form while still being (perhaps ironically) steeped in it.

Q: Perhaps it’s too early to get a clear sense of it, but how do you feel your work has developed? Where do you see your work headed?

A: I used to approach poetry with a sort of bleeding-heart, blood-on-the-page, Hemingway-esqueness coupled with a heavily Ginsberg influenced cadence. Surrealism also had a huge influence on me around 2016/17 and I felt that since then I was always trying to write, read, and figure out what “experimental” or avant-garde poetry was.

While now, I do in some ways have a better sense of it, I do see that I have gone from a more raw, bleeding-heart poetic approach to a more controlled and language-centered one coupling vulnerability with more “objective” or humorous/ironic language (my haiku practice likely also influenced this movement). As one of my former professors, Mary Biddinger, called it, rather than “bleeding on the page, now readers are seeing blood through the gauze” with my more recent poems.

Maybe I’ll head towards a synthesis of these bleeding-heart vs. language-focused poems or maybe I’ve already stumbled into a sort of middle ground. I think my future work could go either way, or maybe in a different direction, which I am also open to.

Q: What has been the process of attempting to shape a manuscript, and what have you been discovering through that process? Are there poems that don’t fit with the shape, or are you leaning more into a kind of catch-all?

A: I think since working on these poems for Double Time, in the Summer and Fall of 2023, I’ve thought a lot more about shaping a manuscript. Perhaps it’s because the manuscript was so rule based and number dependent — on top of the line sequences, each section had a certain number of poems, and the poems all add up to an even number as well — that I’ve since been more willing to cut poems from more recent manuscripts, where I was much less inclined to before with DT. I’d assume that more recent chapbook rejections have also played a role in this.

But overall, sometimes certain poems seem really good once you write them and place them in a manuscript but after a few weeks or months break and a return to them, they don’t land as gracefully as they did before. Perhaps I’m slowly becoming a better editor for myself and my manuscripts.

Q: Are you finding a difference in how you approach attempting to shape a full-length collection vs. a chapbook-sized manuscript?

A: I am finding a difference. I would say once I realized J.H. Prynne, for example, in recent years almost solely releases chapbook-length manuscripts (at an almost intense pace), it gave me some relief and freedom. The freedom to not sit and try to think about ‘what will the next book project be’ but instead think of smaller projects that I feel like I tend to have more stamina or excitement for at the moment. This is also why I sort of gave up trying to write fiction. It isn’t that I think I have a short or ruined attention span or anything but rather that I think I’m more interested in capturing something in language in the moment, or in a short(er) span of time, rather than something in the long term. I don’t doubt that that thinking could also change for me at some point, too; but for now, I tend to be more chapbook-focused.

Q: Finally (and you might have answered an element of this prior), who do you read to reenergize your own work? What particular works can’t you help but return to?

A: Hoa Nguyen, Louis Zukofsky, David Melnick, Lillian-Yvonne Betram, jos charles, Kobayashi Issa, J.H. Prynne — in no particular order. I can’t help but return to Hoa Nguyen’s Violet Energy Ingots, Melnick’s Pcoet, Lillian-Yvonne Bertram’s Travesty Generator, J.H. Prynne’s Orchard, and Zukofsky’s 80 Flowers. I’ve been meaning to return to charles’ feeld because it really floored me and caused things to click in me on multiple poetic and emotional levels the last time I read it but I think I’ve only read it once or twice.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Wednesday, May 28, 2025

Tuesday, May 13, 2025

TtD supplement #276 : seven questions for Misha Solomon

Misha Solomon is a homosexual poet in and of Tiohtià:ke/Montréal. He is the author of two chapbooks, FLORALS (above/ground press, 2020) and Full Sentences (Turret House Press, 2022), and his work has recently appeared in Best Canadian Poetry 2024, Arc Poetry Magazine, The Fiddlehead, Grain, The Malahat Review, and Riddle Fence. His debut full-length collection, My Great-Grandfather Danced Ballet, is forthcoming with Brick Books in 2026.

His poems “(Help Me Choose a Photo of) My Engagement Ring (to Post on Instagram),” “I Didn’t Call My Mother” and “Duplex Duplex” appear in the forty-fifth issue of Touch the Donkey.

Q: Tell me about “(Help Me Choose a Photo of) My Engagement Ring (to Post on Instagram),” “I Didn’t Call My Mother” and “Duplex Duplex.”

A: These three poems have disparate origins, but they’re all explorations of a kind of “queer mundanity” and a discomfort with “growing up” in homonormative ways.

I wrote "(Help Me Choose a Photo of) My Engagement Ring (to Post on Instagram)” for a Hybrid Forms workshop with Sina Queyras during my recent MA at Concordia — we were asked to bring in work to introduce ourselves, and this poem captured a lot of what I was writing and thinking about at the time. It will next appear in my debut full-length, coming from Brick Books in 2026. I wrote “I Didn’t Call My Mother” as part of a writing activity with my fiancé Guillaume Denault. And I wrote “Duplex Duplex,” which owes a debt of gratitude to the form’s creator Jericho Brown, as part of some sort of form-per-day challenge that Carlos Pittella shared with me — I don’t think either of us got past day two or three.

Q: How do these poems compare to some of the other work you’ve been doing lately?

A: These poems are a bit “lighter” than the work I’ve been doing lately. And they’re more grounded in the real and immediate domestic sphere. Lately I’ve been writing weirder, wilder stuff about (non-)reproduction that brings in a lot of animal facts I’ve had rattling around in my brain since I was a child.

Q: What prompted this shift towards a lighter approach, and how do those shifts reveal themselves?

A: For better or for worse (probably for worse), I almost always go into a poem with a “topic” in mind, and the topics of these poems couldn’t be taken too seriously. Maybe “light” is the wrong word. Maybe “seriously” is the wrong word. I guess I just wanted or needed the poems to be a little funny, to poke some fun at their domestic trappings, possibly to allow for some of the underlying emotion to exist within them.

Q: Do you consider this a shift in your writing generally, or more of an expansion?

A: Honestly, I hardly consider it a shift. More of a… modulation. I think humour/darkness/weirdness are each always bubbling under the surface of each of my poems, and I sometimes let one or more of them… come to a boil? Humour is particularly difficult for me to modulate. I’ve been told I use it to undercut emotion. I’m not how much of that is conscious.

Q: Do you have any models for the types of work you’ve been attempting? Any particular writers or works at the back of your head as you write?

A: Frank O’Hara, always. Danez Smith has been in my head a lot lately, especially after having had the pleasure of working with them at Banff earlier this year. And lately I’ve been thinking a lot about Nate Lippens’s writing, after devouring his two short novels My Dead Book and Ripcord.

Q: With two published chapbooks and a full-length debut forthcoming, as well as your current works-in-progress, how do you feel your work has developed? Where do you see your work heading?

A: I feel that I’ve moved away from try to engineer or engender a certain reaction (usually shock) in a reader. I try to give in to mystery and open-endedness, and to bring in more and more research-creation. I see my work, or at least I hope I see my work, heading to a place that is at once formless and accessible, that doesn’t fit neatly into any categories but can be relatively widely read and enjoyed.

Q: Finally, who do you read to reenergize your own work? What particular works can’t you help but return to?

A: Sorry for the delay on this last answer, I had to go to my spin class. (Do NOT edit this out. Your readers need to know that I am newly very into spinning.)

Because of my ongoing desire to “complete tasks” due to an obsessive, productivity-pilled mind, I rarely return to works. Am I allowed to admit that? I think Grease and The Wizard of Oz are the only movies I have seen multiple times. Anyway — to reenergize my work, I read a poem from The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara and use some element of the poem as a prompt. Also, I take workshops and studios to reenergize my work — I always love Sarah Burgoyne’s poetry studios, which have been immensely inspiring and productive for me. Recently, I took a great workshop with Susan Gillis hosted by the QWF, and I’ll be taking one with Jay Ritchie this spring. I also have a generative poetry group (with André Babyn and Sasha Manoli) and a workshop/reading group (with Madelaine Caritas Longman, Patrick O’Reilly, Carlos Pittella, Melanie Power, and Sarah Wolfson) and the work of all those incredible poets is always reenergizing. I also read non-poetic work to power my work — lately that’s been stuff like Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire, edited by Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson.

His poems “(Help Me Choose a Photo of) My Engagement Ring (to Post on Instagram),” “I Didn’t Call My Mother” and “Duplex Duplex” appear in the forty-fifth issue of Touch the Donkey.

Q: Tell me about “(Help Me Choose a Photo of) My Engagement Ring (to Post on Instagram),” “I Didn’t Call My Mother” and “Duplex Duplex.”

A: These three poems have disparate origins, but they’re all explorations of a kind of “queer mundanity” and a discomfort with “growing up” in homonormative ways.

I wrote "(Help Me Choose a Photo of) My Engagement Ring (to Post on Instagram)” for a Hybrid Forms workshop with Sina Queyras during my recent MA at Concordia — we were asked to bring in work to introduce ourselves, and this poem captured a lot of what I was writing and thinking about at the time. It will next appear in my debut full-length, coming from Brick Books in 2026. I wrote “I Didn’t Call My Mother” as part of a writing activity with my fiancé Guillaume Denault. And I wrote “Duplex Duplex,” which owes a debt of gratitude to the form’s creator Jericho Brown, as part of some sort of form-per-day challenge that Carlos Pittella shared with me — I don’t think either of us got past day two or three.

Q: How do these poems compare to some of the other work you’ve been doing lately?

A: These poems are a bit “lighter” than the work I’ve been doing lately. And they’re more grounded in the real and immediate domestic sphere. Lately I’ve been writing weirder, wilder stuff about (non-)reproduction that brings in a lot of animal facts I’ve had rattling around in my brain since I was a child.

Q: What prompted this shift towards a lighter approach, and how do those shifts reveal themselves?

A: For better or for worse (probably for worse), I almost always go into a poem with a “topic” in mind, and the topics of these poems couldn’t be taken too seriously. Maybe “light” is the wrong word. Maybe “seriously” is the wrong word. I guess I just wanted or needed the poems to be a little funny, to poke some fun at their domestic trappings, possibly to allow for some of the underlying emotion to exist within them.

Q: Do you consider this a shift in your writing generally, or more of an expansion?

A: Honestly, I hardly consider it a shift. More of a… modulation. I think humour/darkness/weirdness are each always bubbling under the surface of each of my poems, and I sometimes let one or more of them… come to a boil? Humour is particularly difficult for me to modulate. I’ve been told I use it to undercut emotion. I’m not how much of that is conscious.

Q: Do you have any models for the types of work you’ve been attempting? Any particular writers or works at the back of your head as you write?

A: Frank O’Hara, always. Danez Smith has been in my head a lot lately, especially after having had the pleasure of working with them at Banff earlier this year. And lately I’ve been thinking a lot about Nate Lippens’s writing, after devouring his two short novels My Dead Book and Ripcord.

Q: With two published chapbooks and a full-length debut forthcoming, as well as your current works-in-progress, how do you feel your work has developed? Where do you see your work heading?

A: I feel that I’ve moved away from try to engineer or engender a certain reaction (usually shock) in a reader. I try to give in to mystery and open-endedness, and to bring in more and more research-creation. I see my work, or at least I hope I see my work, heading to a place that is at once formless and accessible, that doesn’t fit neatly into any categories but can be relatively widely read and enjoyed.

Q: Finally, who do you read to reenergize your own work? What particular works can’t you help but return to?

A: Sorry for the delay on this last answer, I had to go to my spin class. (Do NOT edit this out. Your readers need to know that I am newly very into spinning.)

Because of my ongoing desire to “complete tasks” due to an obsessive, productivity-pilled mind, I rarely return to works. Am I allowed to admit that? I think Grease and The Wizard of Oz are the only movies I have seen multiple times. Anyway — to reenergize my work, I read a poem from The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara and use some element of the poem as a prompt. Also, I take workshops and studios to reenergize my work — I always love Sarah Burgoyne’s poetry studios, which have been immensely inspiring and productive for me. Recently, I took a great workshop with Susan Gillis hosted by the QWF, and I’ll be taking one with Jay Ritchie this spring. I also have a generative poetry group (with André Babyn and Sasha Manoli) and a workshop/reading group (with Madelaine Caritas Longman, Patrick O’Reilly, Carlos Pittella, Melanie Power, and Sarah Wolfson) and the work of all those incredible poets is always reenergizing. I also read non-poetic work to power my work — lately that’s been stuff like Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire, edited by Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson.

Friday, May 2, 2025

TtD supplement #275 : eight questions for Jordan Davis

Jordan Davis’s books include Shell Game (2017), Noise (2023) and Yeah, No (2023); he has edited several publications including The Poetry Project Newsletter, The Hat, Teachers & Writers, The Collected Fiction of Kenneth Koch, The Collected Poems of Kenneth Koch, the Apple iOS journal Ladowich, CCCP Chapbooks, several titles for Subpress Collective, and most recently a monthly publishing poetry on “Jewish-ish themes,” The Nu Review. He is also a former poetry editor of The Nation.

An excerpt from his “the book of how’s that going to work” appears in the forty-fifth issue of Touch the Donkey.

Q: Tell me about the work-in-progress “the book of how’s that going to work.”

A: I’ve had this notebook since the early 90s, absurdly thick cover, banana paper with threads and dirt-like imperfections in the surface, the absolute opposite of something too nice to write in, but not junk either, and I’ve carried it to five or six different homes thinking “someday I’ll know what to do with this.” That didn’t happen, so I wrote every wrong thing I could think of.

Q: How do these poems compare with some of the other work you’ve been doing lately?

A: These poems exist, which is a significant difference.

Q: Is utilizing the notebook the usual way your poems, and your projects, begin? How do poems move from notebook to completed?

A: It is. I get to the end of the notebook, and then I see what’s there.

Q: Do you see a difference in how poems emerge through working the notebook, versus any other process? And what other processes might you use to compose work?

A: Every notebook does act on my brain like a specific kind of container, and what I find congenial at one time may turn out later to be too confining or too expansive. Time is the real constraint — I use what I can find when the time emerges. Index cards… let’s talk about that another time.

Q: Did the shapes of your notebook pages inform the shapes of your poems? I’m thinking of those long, thin poems by William Carlos Williams, as he composed first drafts on his prescription pads.

A: These poems, yes. I want the work to be shapely but it’s the shape of the mental object I care about — the pathway of the experience of the poem. Other poems, the notebook acts more as a collecting plate, a radio telescope.

Q: With a handful of published books and chapbooks under your belt, how do you feel your work has developed? Where do you see your work headed?

A: I go where the thing I have to say is, but I haven’t liked to go where the things I dislike are. I’ll probably have to wade into what I dislike now. And there’s so much to dislike.

Q: I’m curious as to what some of that “wading into what you dislike” might look like, and what the process and results might be. Should I even ask?

A: I see a lot of a willed kind of poetry — self-seeking, self-mythologizing… often pretty but in a way you see coming. It clearly serves a need, but at the expense of deeper needs, in my opinion.

Q: Finally, who do you read to reenergize your own work? What particular works can’t you help but return to?

A: Poetry, if it’s any good at all, is for rereading. I’ve been rereading Kenneth Koch; it was just his centenary (February 27). I find something new every time I read him. For me, editing books and chapbooks by other poets is a form of rereading that helps me see what I want better. What renews my love of poetry, or rather, what gives me the feeling I enjoy most, is to find new poets I want to reread.

An excerpt from his “the book of how’s that going to work” appears in the forty-fifth issue of Touch the Donkey.

Q: Tell me about the work-in-progress “the book of how’s that going to work.”

A: I’ve had this notebook since the early 90s, absurdly thick cover, banana paper with threads and dirt-like imperfections in the surface, the absolute opposite of something too nice to write in, but not junk either, and I’ve carried it to five or six different homes thinking “someday I’ll know what to do with this.” That didn’t happen, so I wrote every wrong thing I could think of.

Q: How do these poems compare with some of the other work you’ve been doing lately?

A: These poems exist, which is a significant difference.

Q: Is utilizing the notebook the usual way your poems, and your projects, begin? How do poems move from notebook to completed?

A: It is. I get to the end of the notebook, and then I see what’s there.

Q: Do you see a difference in how poems emerge through working the notebook, versus any other process? And what other processes might you use to compose work?

A: Every notebook does act on my brain like a specific kind of container, and what I find congenial at one time may turn out later to be too confining or too expansive. Time is the real constraint — I use what I can find when the time emerges. Index cards… let’s talk about that another time.

Q: Did the shapes of your notebook pages inform the shapes of your poems? I’m thinking of those long, thin poems by William Carlos Williams, as he composed first drafts on his prescription pads.

A: These poems, yes. I want the work to be shapely but it’s the shape of the mental object I care about — the pathway of the experience of the poem. Other poems, the notebook acts more as a collecting plate, a radio telescope.

Q: With a handful of published books and chapbooks under your belt, how do you feel your work has developed? Where do you see your work headed?

A: I go where the thing I have to say is, but I haven’t liked to go where the things I dislike are. I’ll probably have to wade into what I dislike now. And there’s so much to dislike.

Q: I’m curious as to what some of that “wading into what you dislike” might look like, and what the process and results might be. Should I even ask?

A: I see a lot of a willed kind of poetry — self-seeking, self-mythologizing… often pretty but in a way you see coming. It clearly serves a need, but at the expense of deeper needs, in my opinion.

Q: Finally, who do you read to reenergize your own work? What particular works can’t you help but return to?

A: Poetry, if it’s any good at all, is for rereading. I’ve been rereading Kenneth Koch; it was just his centenary (February 27). I find something new every time I read him. For me, editing books and chapbooks by other poets is a form of rereading that helps me see what I want better. What renews my love of poetry, or rather, what gives me the feeling I enjoy most, is to find new poets I want to reread.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)