Julia Drescher is the author of Open Epic (Delete Press, 2017). Recent work has appeared in Entropy, Likestarlings, Aspasiology, The New New Corpse, & Hotel. She lives in Colorado where she co-edits the press Further Other Book Works with the poet C.J. Martin.

A selection of pieces “from LOUD OBJECT” appear in the twenty-second issue of Touch the Donkey.

Q: Tell me about the sequence “LOUD OBJECT.”

A: I once thought of it as “failed-essay-as-poem” but that’s not *quite* right…

Generally, I am always thinking about (troubling) reading/being a (troubled) reader. So it splayed out from initially (mis)hearing a kind of “broadcast” between 1. readings of various texts of Frances Boldereff (particularly the letters to Olson & Let Me Be Los), which I was thrown back thru by 2. readings of Clarice Lispector’s The Passion According to G.H. & stories like “The Message” & “The Egg & the Chicken”.

Parts of the book On Hysteria: The Invention of a Medical Category between 1670 and 1820 by Sabine Arnaud are also present (as making up most-but not all- of the direct quotes in the poem).

“Loud Object” as a title is borrowed from Lispector, but (apparently!) filtered through the kind of mistake I am always making which is conflating things I have read: I had it in my head that this was Lispector’s working title for The Passion…. but actually it was for Água Viva.

Also, I didn’t realize it at the time, but Lisa Robertson’s “Time in the Codex” absolutely accompanies/is a vital haunting of “LOUD OBJECT”.

Q: How do these poems compare to some of the other work you’ve been doing lately?

A: Hard to say. Repetition with difference? (hopefully)

I mean, collaging, sound (& the mishearing of things), a fraught relation with the sentence/essaying, will probably always be the spit in the instrument, so to speak.

I’ve been thinking a lot about (tip)trees & dilative (dispersive) movements lately.

Q: There are plenty of examples of those who use poems as their thinking forms, composing works that could easily be described as essay-poems or poem-essays, from Erín Moure to Elisa Gabbert to Lisa Robertson to Jennifer Moxley, among so many others. Why would you think “LOUD OBJECT” as a “failed-essay-as-poem”?

A: I guess what I mean is that where “LOUD OBJECT” might exceed what I think, it refuses any desire for subjectivity in a de/generative way. I want to say that the poem(essay) uses me, thinks through me (when, that is, I don’t refuse this refusal)—which is how “poem” & “essay” muddle/get muddled. I’m also just thinking of/trying to think through the feeling that reading gives where there is an inability (a “failure”) to distinguish the object (the text that is read? the reader? etc.) from the “agencies of observation” (the text that is read? the reader? etc.)--a physics formulation that I am very much mishandling I’m sure.

So I wasn’t necessarily saying “failure” in the “traditional” sense I suppose?

Q: I like the idea of a poem exceeding what the author might think, which is reminiscent, slightly, of Jack Spicer’s belief that he was merely a conduit for poems. Where do you see yourself on such a spectrum, between “author” and “conduit”? Are your poems collaborations between your hand and where the poem itself wishes to go?

A: At the best of times, [Julia] is a wave of tendencies the poem makes use of.

At the best of times, anything like “my hand”—which would probably also be “in spite of my hand”—would be a legion of other hands—a Niagara effect (you know, impossible to list). I guess that’s closer to conduit—author as revered subject-state doesn’t interest me (& would—for me—perhaps be closer to an idea of “failure” in that traditional sense).

When I think about this question, the formulation—which could only ever be a fluidity—that I would want to work under would include, but not be at all be limited to; Moten, Robertson, Dickinson, Spicer, Mendieta, Hampton, Bess, Lispector, Boldereff, Arsić, Howe, Weil, Eastman, Kafka (via Paul North) Niedecker, Bower birds….

That is to say (at the best of times) the poem as how you somehow “collaborate” —in spite of yourself— where you somehow are in this “intimacy without proximity” conversation going on.

However/also I feel Spicer’s “all hook, no bait” very seriously—so the only caveat I think I have to the conduit/radio/more+less would be: same as ‘the muse’ formulations, I don’t think this means that you’re completely “off the hook” for the shit you say or do. You know, when it exceeds—again—is when it does so despite your individuation, & when it doesn’t—that’s when you’ve got to “answer for it”, be response-able, etc etc.

Q: With a handful of chapbooks and a full-length collection under your belt, how do you feel your work has developed? Where do you see your work headed?

A: To stay a beginner, an amateur. All belts are off.

Q: How do poems/projects usually begin for you? Do you work with loose ideas of what you wish to accomplish, whether thematically, structurally or with an idea, or do you begin with collage and feel out where the poem goes?

A: I generally wait (which is a listening/looking for) things to strike me—this can usually be anything/anyone--any text: an encounter with reading I am led to, with “the natural” world, an artwork, music, etc. These would be encounters that “show me the door” – in all the valences of that phrase. Who & what I want to think with (which is to feel with) I suppose. But any of this always has any other encounters that came before, so it’s all mixed up. This isn’t to say I don’t start with “my own idea”, but it seems like I do so *in order to* be thwarted—I don’t know if this is just temperament or what, but I don’t necessarily have an accomplishment in mind—except maybe to continue to be shown the door.

Q: Finally, who do you read to reenergize your own work? What particular works can’t you help but return to?

A: Other than the people I mentioned above, really it is impossible to list as it is expanding all the time—not to be facetious, but it would just have to be pictures of my bookshelves! I will say, too, that I go in & out of consciousness of this, but in terms of energy & return & just all over my work, I have always been--or also always returning to--my immediate family. In such wonderful de/generative ways, both my parents can really twist some language up!

Monday, July 29, 2019

Monday, July 15, 2019

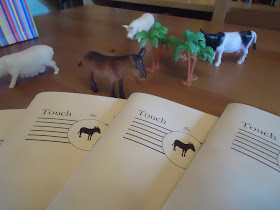

Touch the Donkey : twenty-second issue,

The twenty-second issue is now available, with new poems by Julia Drescher, Biswamit Dwibedy, Aja Couchois Duncan, José Felipe Alvergue, Roxanna Bennett, Conyer Clayton and Emily Izsak.

Eight dollars (includes shipping). You haven’t found me work in 12 years.

Eight dollars (includes shipping). You haven’t found me work in 12 years.

Wednesday, July 3, 2019

TtD supplement #137 : seven questions for Michael Cavuto

Michael Cavuto is a poet living in Queens. His first book, Country Poems, will be published in early 2020 with Knife Fork Books in Toronto. With Dale Smith & Hoa Nguyen, he edits the Slow Poetry in America Newsletter.

His poem “PYRE II” appears in the twenty-first issue of Touch the Donkey. His poem “PYRE III” is scheduled to appear in the twenty-third issue of Touch the Donkey.

Q: Tell me about the poems “PYRE II” and “PYRE III.”

A:

Pyre III is a poem that does and does not yet exist. When I started writing the Pyre poems two years ago, it was in the space of a very important poet’s passing, and I was taken up with the poem’s particular capacity for remembering – so in that way, the first Pyre poem was a kind of elegy. In writing through an experience of poetic memory, I engage with a distinct kind of time unique to poetry.

In the poem there is a different time, but it does not come into confrontation with lived experience as contrary to ordinary time. Rather, the poem enfolds time & the past and passing are held in its moment. Change becomes the poem’s capacity for remembering.

Since beginning to write these Pyre poems, I’ve given them over to what seems to me to be a kind of reverent patience. In finding memory to be the force of these poems, I’ve come to understand their movement as an ellipsis, as something that stretches out from absence in the shape of return.

So, perhaps to be more direct, since beginning to write these Pyre poems, I have returned to them each year, one year after the previous poem was written, to experience the poem again as a remembrance, and to record a new memory as I find it there, written only from elements in the original poem. Pyre III will be written in March, and I’m sure that I’ll find these poems quite changed from a year ago, from two years ago.

I began these poems as one would stacking rocks for the dead, and I return to them each year to witness their change.

& now I’m thinking of this as a kind of completeness that poetic memory offers to lived experience

& earlier tonight I heard Will Alexander read and he said the poem must exist in total reality, &

then following him, Cecilia Vicuña :

& now we’re aware that everything is going away

The Pyre poems are a record of loss held, of total change as presence. These stones stacked for the dead cling to life as it goes on living.

now I think of Paul Metcalf, in Genoa, of ancient signs of passing time:

and there was Sargasso weed, rumored to trap ships as in a web … detritus, perhaps, of Atlantis …

Q: How do these poems compare to some of the other work you’ve been doing lately?

A:

All of my poems exist in sequences, so compositionally the Pyre poems (which will comprise Pyre I ¬– X) relate to the other poems I’ve been writing for the past five or so years. This way poems are always imperfect and incomplete, moving outside of the boundaries of a single poem and in larger resonance with other perceptions. But the Pyre poems are exaggerated across time, tracing the contours of memory as they push out on present experience.

In these poems, too, I continue what I’ve found essential in my writing, to take in no obscured way other poets as my guides, and to follow this hearing as the attentive force of the poem.

Q: What is it about the sequence that appeals? What do you feel you can accomplish through a structure that might not be possible otherwise?

A:

Writing in sequences acts as a detour around some of the more ordinary limitations of the poem – such as completeness. It’s a matter of finding and mixing sources as a way of locating myself, which sequences seem to do inherently through their constellating of many instances at once. Like daily life, sequences are made of fragmentary and divergent gleanings.

The sequence is an alchemical process of accumulation insofar as reading and writing across the poems is transformational. Poems, words, and images change as they come into relation with each other, and new vocabularies emerge. In this way, the structure of the sequence is always in flux. Sequences seem to ask the very question of poetic movement, of the utterance in a continued state of extension and refiguration, insisting on silent boundaries as porous thresholds.

Q: What influences have brought you to the ways in which you approach writing? What writers and/or works have changed the way you think of your work?

A: Far and beyond, in an incommensurable, entirely incommunicable way, Dale Smith and Hoa Nguyen have been my most important guides, as well as two friends I love deeply and whose works and lives as poets I couldn’t be more committed to. When I moved to Toronto at 20, JenMarie Macdonald told me to get in touch with them. We connected quickly over shared admirations: Baraka, Niedecker, Whalen, Bernadette Mayer – our shared interests in community-making through poetry. At a certain point, I was going for near-weekly dinners at their house in the Danforth, and we’d stay up late talking poetry, music, gossip. Our Slow Poetry in American Newsletter came out of those conversations.

At the same time, Hoa began to influence an important shift in my thinking away from any idea of lineage and to thinking in constellations of writers and artists, of configurations of influences, chance echoes, and engagements in constant motion…. Guides shift in purpose and proximity given the needed attentions of a particular moment. These constellations are a kind of trans-historical community in poetry.

The people who hold the most important places in my life as a poet have been those writers and artists with whom I’ve developed relationships grounded in generative, creative and excessive forms of friendship and affection: the poets Hamish Ballantyne and Tessa Bolsover, Fan Wu, Julian Butterfield, Alex MacKay, Marion Bell (whose book Austerity is an vital gift to the world), the actual angel, Alex Kulick. Poet-turned-gambler, great magic-grifter Iris Liu. It’s really nice to say the names of friends. I think Bill Berkson said I write poems so I can say things to my friends, or I hope he said that.

Q: With a first trade collection forthcoming in 2020, how do you feel your work has developed?

Where do you see your work headed?

A: Most of the development in my work has been a patient finding, an attunement to right hearing of the poems as they have to be, which is full of imperfection and fragmentation. As a very young poet, I tried more than anything to avoid at all costs any semblance of narrative, and through my first book, Country Poems, I’ve come to realize that telling stories is at the forefront of all of my poetry. Of course, narrative and stories aren’t the same thing, but it’s been a surprise. Country Poems, I hope, begins in some nebulous proximity to the lyric and unravels over uncertain ground into forms of attention and articulation much less discernable. Lyrically, I’ve made my task to decenter the self in relation to the utterance, to locate in the poem a nexus of converging voices and images, receptions and articulations. Most importantly, in beginning to learn the scope of a book of poems, I’ve gotten closer to the transformative force within poetic experience: a distinct vocabulary emerging in echoes and refractions across a group – or in the case of Country Poems, many groups – of poems.

I’m working now on a sequence of poems that tell the tall tale of HB, a shadow of the doomed figure Hamish Ballantyne whose demise is told in a ballad that opens Country Poems. So, in some non-linear way, this new sequence, The Comings of HB, precedes Country Poems. Poems, as far as I can tell, take place in a multitude of nows quite different from our ordinary experience of lived time, so I’m learning about how poems interact temporally, and how to hold these spheres of time in nearness to each other. I think of the title to Joanne Kyger’s collected poems often, About Now. Every poem in that book is happening right now.

I’m thinking a lot about collaboration as an important form of decentering.

Q: What do you mean by “decentering”? How do you see that emerging through the process of collaboration?

A: Thinking about the poem as a nexus of convergences and divergences, as an experience in itself. I’m interested in decentering the self within the poem: finding the self to be only one – and not necessarily the primary – element within the work. Stein comes to mind, but I don’t think this a directly Steinian idea. Duncan’s notion of derivation is important, of a sensitivity to voices and histories that weigh on present lived experience. Kyger talks about the poem as a record of the particularities of a life. If my poems take those stakes seriously, and I hope they do, then they do this through a kind of active locating of the self among many forces that are not necessarily identical, or even clearly in relation, to the self. Decentering as I think of it moves away from expression in the older sense – through literary projection, through stories & images & histories, through secrets & obscurities, it’s a way of searching for entirely new forms of the self that leave behind any essential idea of individuality. It makes me think about the sequence again, and of course, the constellation. Today Tessa said the crystalline, which is exactly it.

I don’t want to theorize it much beyond that, because it’s happening and unfolding in the poems, and I feel there’s a lot of work ahead. But, yes, collaboration, again as a form of community – the very gesture of collective creativity. In this new group of poems, The Comings of HB, which really is a work of dubiously authored songs, there’s an idea for there to be texts from other writers among the poems, texts that only deepen and amplify the questions around this figure, HB, which really are questions posed through poems that try to push on the edges of storytelling.

Q: Finally, who do you read to reenergize your own work? What particular works can’t you help but return to?

A: Among the many writers I’ve invoked already, there are so many others that I hold dear to my work: Stacy Szymaszek, M. NourbeSe Philip, John Wieners, Susan Howe, Nate Mackey, HD, Spicer, Paul Blackburn & Ed Sanders, Lucia Berlin. Cesare Pavese. Huidobro, Alejandra Pizarnik, Bolaño… Lezama. Dickinson. These poets take in the world and are taken in by it, so it’s endless…

Mostly, in the intimacy of returning, I read my friends.

Thanks so much for this conversation, rob.

His poem “PYRE II” appears in the twenty-first issue of Touch the Donkey. His poem “PYRE III” is scheduled to appear in the twenty-third issue of Touch the Donkey.

Q: Tell me about the poems “PYRE II” and “PYRE III.”

A:

Pyre III is a poem that does and does not yet exist. When I started writing the Pyre poems two years ago, it was in the space of a very important poet’s passing, and I was taken up with the poem’s particular capacity for remembering – so in that way, the first Pyre poem was a kind of elegy. In writing through an experience of poetic memory, I engage with a distinct kind of time unique to poetry.

In the poem there is a different time, but it does not come into confrontation with lived experience as contrary to ordinary time. Rather, the poem enfolds time & the past and passing are held in its moment. Change becomes the poem’s capacity for remembering.

Since beginning to write these Pyre poems, I’ve given them over to what seems to me to be a kind of reverent patience. In finding memory to be the force of these poems, I’ve come to understand their movement as an ellipsis, as something that stretches out from absence in the shape of return.

So, perhaps to be more direct, since beginning to write these Pyre poems, I have returned to them each year, one year after the previous poem was written, to experience the poem again as a remembrance, and to record a new memory as I find it there, written only from elements in the original poem. Pyre III will be written in March, and I’m sure that I’ll find these poems quite changed from a year ago, from two years ago.

I began these poems as one would stacking rocks for the dead, and I return to them each year to witness their change.

& now I’m thinking of this as a kind of completeness that poetic memory offers to lived experience

& earlier tonight I heard Will Alexander read and he said the poem must exist in total reality, &

then following him, Cecilia Vicuña :

& now we’re aware that everything is going away

The Pyre poems are a record of loss held, of total change as presence. These stones stacked for the dead cling to life as it goes on living.

now I think of Paul Metcalf, in Genoa, of ancient signs of passing time:

and there was Sargasso weed, rumored to trap ships as in a web … detritus, perhaps, of Atlantis …

Q: How do these poems compare to some of the other work you’ve been doing lately?

A:

All of my poems exist in sequences, so compositionally the Pyre poems (which will comprise Pyre I ¬– X) relate to the other poems I’ve been writing for the past five or so years. This way poems are always imperfect and incomplete, moving outside of the boundaries of a single poem and in larger resonance with other perceptions. But the Pyre poems are exaggerated across time, tracing the contours of memory as they push out on present experience.

In these poems, too, I continue what I’ve found essential in my writing, to take in no obscured way other poets as my guides, and to follow this hearing as the attentive force of the poem.

Q: What is it about the sequence that appeals? What do you feel you can accomplish through a structure that might not be possible otherwise?

A:

Writing in sequences acts as a detour around some of the more ordinary limitations of the poem – such as completeness. It’s a matter of finding and mixing sources as a way of locating myself, which sequences seem to do inherently through their constellating of many instances at once. Like daily life, sequences are made of fragmentary and divergent gleanings.

The sequence is an alchemical process of accumulation insofar as reading and writing across the poems is transformational. Poems, words, and images change as they come into relation with each other, and new vocabularies emerge. In this way, the structure of the sequence is always in flux. Sequences seem to ask the very question of poetic movement, of the utterance in a continued state of extension and refiguration, insisting on silent boundaries as porous thresholds.

Q: What influences have brought you to the ways in which you approach writing? What writers and/or works have changed the way you think of your work?

A: Far and beyond, in an incommensurable, entirely incommunicable way, Dale Smith and Hoa Nguyen have been my most important guides, as well as two friends I love deeply and whose works and lives as poets I couldn’t be more committed to. When I moved to Toronto at 20, JenMarie Macdonald told me to get in touch with them. We connected quickly over shared admirations: Baraka, Niedecker, Whalen, Bernadette Mayer – our shared interests in community-making through poetry. At a certain point, I was going for near-weekly dinners at their house in the Danforth, and we’d stay up late talking poetry, music, gossip. Our Slow Poetry in American Newsletter came out of those conversations.

At the same time, Hoa began to influence an important shift in my thinking away from any idea of lineage and to thinking in constellations of writers and artists, of configurations of influences, chance echoes, and engagements in constant motion…. Guides shift in purpose and proximity given the needed attentions of a particular moment. These constellations are a kind of trans-historical community in poetry.

The people who hold the most important places in my life as a poet have been those writers and artists with whom I’ve developed relationships grounded in generative, creative and excessive forms of friendship and affection: the poets Hamish Ballantyne and Tessa Bolsover, Fan Wu, Julian Butterfield, Alex MacKay, Marion Bell (whose book Austerity is an vital gift to the world), the actual angel, Alex Kulick. Poet-turned-gambler, great magic-grifter Iris Liu. It’s really nice to say the names of friends. I think Bill Berkson said I write poems so I can say things to my friends, or I hope he said that.

Q: With a first trade collection forthcoming in 2020, how do you feel your work has developed?

Where do you see your work headed?

A: Most of the development in my work has been a patient finding, an attunement to right hearing of the poems as they have to be, which is full of imperfection and fragmentation. As a very young poet, I tried more than anything to avoid at all costs any semblance of narrative, and through my first book, Country Poems, I’ve come to realize that telling stories is at the forefront of all of my poetry. Of course, narrative and stories aren’t the same thing, but it’s been a surprise. Country Poems, I hope, begins in some nebulous proximity to the lyric and unravels over uncertain ground into forms of attention and articulation much less discernable. Lyrically, I’ve made my task to decenter the self in relation to the utterance, to locate in the poem a nexus of converging voices and images, receptions and articulations. Most importantly, in beginning to learn the scope of a book of poems, I’ve gotten closer to the transformative force within poetic experience: a distinct vocabulary emerging in echoes and refractions across a group – or in the case of Country Poems, many groups – of poems.

I’m working now on a sequence of poems that tell the tall tale of HB, a shadow of the doomed figure Hamish Ballantyne whose demise is told in a ballad that opens Country Poems. So, in some non-linear way, this new sequence, The Comings of HB, precedes Country Poems. Poems, as far as I can tell, take place in a multitude of nows quite different from our ordinary experience of lived time, so I’m learning about how poems interact temporally, and how to hold these spheres of time in nearness to each other. I think of the title to Joanne Kyger’s collected poems often, About Now. Every poem in that book is happening right now.

I’m thinking a lot about collaboration as an important form of decentering.

Q: What do you mean by “decentering”? How do you see that emerging through the process of collaboration?

A: Thinking about the poem as a nexus of convergences and divergences, as an experience in itself. I’m interested in decentering the self within the poem: finding the self to be only one – and not necessarily the primary – element within the work. Stein comes to mind, but I don’t think this a directly Steinian idea. Duncan’s notion of derivation is important, of a sensitivity to voices and histories that weigh on present lived experience. Kyger talks about the poem as a record of the particularities of a life. If my poems take those stakes seriously, and I hope they do, then they do this through a kind of active locating of the self among many forces that are not necessarily identical, or even clearly in relation, to the self. Decentering as I think of it moves away from expression in the older sense – through literary projection, through stories & images & histories, through secrets & obscurities, it’s a way of searching for entirely new forms of the self that leave behind any essential idea of individuality. It makes me think about the sequence again, and of course, the constellation. Today Tessa said the crystalline, which is exactly it.

I don’t want to theorize it much beyond that, because it’s happening and unfolding in the poems, and I feel there’s a lot of work ahead. But, yes, collaboration, again as a form of community – the very gesture of collective creativity. In this new group of poems, The Comings of HB, which really is a work of dubiously authored songs, there’s an idea for there to be texts from other writers among the poems, texts that only deepen and amplify the questions around this figure, HB, which really are questions posed through poems that try to push on the edges of storytelling.

Q: Finally, who do you read to reenergize your own work? What particular works can’t you help but return to?

A: Among the many writers I’ve invoked already, there are so many others that I hold dear to my work: Stacy Szymaszek, M. NourbeSe Philip, John Wieners, Susan Howe, Nate Mackey, HD, Spicer, Paul Blackburn & Ed Sanders, Lucia Berlin. Cesare Pavese. Huidobro, Alejandra Pizarnik, Bolaño… Lezama. Dickinson. These poets take in the world and are taken in by it, so it’s endless…

Mostly, in the intimacy of returning, I read my friends.

Thanks so much for this conversation, rob.